Donate

The Many Ways You Can Support the Maritime Museum of San Diego

Your support through donations and membership plays a vital role in maintaining these treasured vessels and keeping their stories alive for future generations.

Join in the adventure!

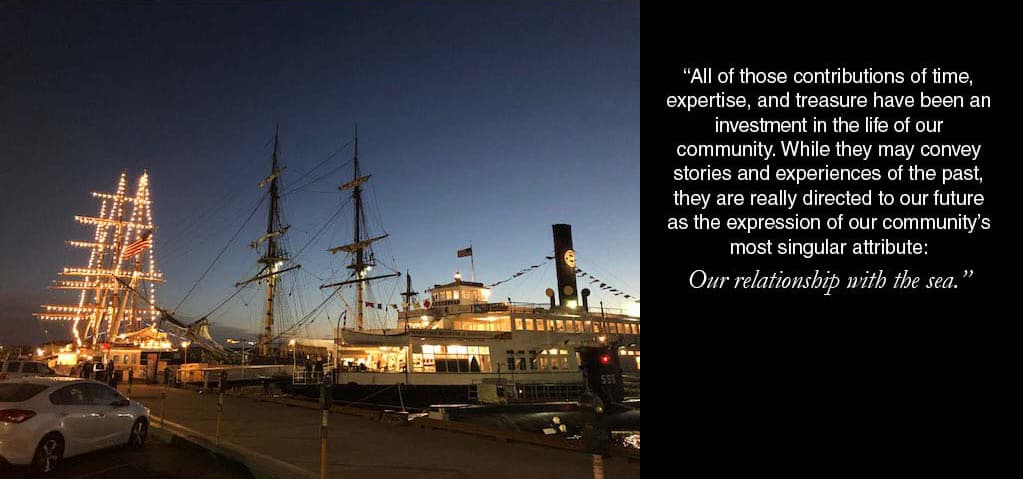

The Maritime Museum of San Diego is home to the maritime story of the West Coast and beyond with one of the most extensive collections of historic ships in the world. Donations & Membership help to tell the maritime story and to preserve these ships.

Support the Maritime Museum of San Diego: Many Ways to Give

Your generous donations help preserve the rich maritime heritage we share with the community. Choose the giving option that works best for you:

Unrestricted Donations

These gifts provide the greatest flexibility, allowing us to address the Museum’s most pressing needs and support day-to-day operations.

Restricted Donations

Prefer to support a specific ship or project? Restricted donations ensure your gift is directed to the area you care about most.

Planned Giving

Leave a lasting legacy while enjoying potential tax benefits. Learn more about how planned giving can support the Museum’s future.

To learn about:

- Donor Stories

- Gift Options

- Personal Planner

- Washington News

Learn More About Planned Giving

If you have any questions about the best way for you to benefit through a planned gift, please call. A member of our Planned Giving Team will be glad to help you. Contact Development at 619-234-9153 x 126

Every gift makes a difference. Whether large or small, your contributions combine to fuel our mission. Join us at any level and become part of this extraordinary journey!

Make a 100% tax-deductible investment to the Maritime Museum’s mission of preserving our history and you are investing in your communities future.

Or send your donation to:

Maritime Museum of San Diego

1492 N Harbor Drive

San Diego, CA 92101